The Feasts of Israel: Foreshadowing the Messiah

Therefore let no one pass judgment on you in questions of food and drink or with regard to a festival or a new moon or a sabbath. These are only a shadow of what is to come; but the substance belongs to Christ. (Col 2:16-17)

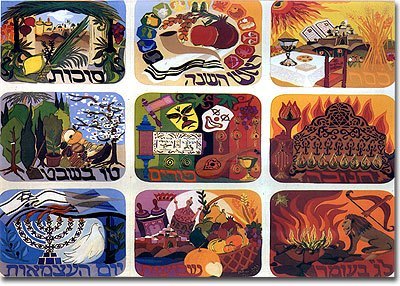

The Jewish feasts commemorate God's sovereign deliverance of the Israelites from Egypt and his care for them throughout the Exodus until their arrival in the Promised Land. Yet as important as these holy days are for the Jews, they are also significant for Christians. As St. Paul writes, they are "a shadow of what is to come," that is, they foreshadow God's plan of salvation for the world in Christ. This article examines the meaning of the Jewish feasts, along with their messianic and typological fulfillment for Christians.

We will first discuss the seven Mosaic Festivals introduced in the Torah, followed by a brief discussion of two post-mosaic festivals.

The Mosaic Festivals

Three times a year all your males shall appear before the LORD your God at the place which he will choose: at the feast of unleavened bread, at the feast of weeks, and at the feast of booths. They shall not appear before the LORD empty-handed; every man shall give as he is able, according to the blessing of the LORD your God which he has given you. (Deut 16:16-17)

Israel's liturgical calendar comprises seven divinely appointed festivals. As outlined in Leviticus 23, these feasts are grouped in three major seasons: in the early spring, the last spring, and the fall:

- The Feast of Passover (Lev 23:4-5)

- The Feast of Unleavened Bread (Lev 23:6-8)

- The Feast of the Sheaf of Firstfruits (Lev 23:9-14)

- The Feast of Weeks/Pentecost (Lev 23:15-22)

- The Feast of Trumpets (Lev 23:23-25)

- The Feast Day of Atonement (Lev 23:26-32)

- The Feast of Booths or Tabernacles (Lev 23:33-44)

Let’s look at the meaning of these seven feasts within the Jewish liturgical year and in the broader context of salvation history.

The Feast of Passover (Pesach)

For Christ, our Passover Lamb, has been sacrificed. (1 Cor 5:7)

The first Jewish feast is the Passover, celebrated on the fourteenth day of the first month of the Jewish calendar (Aviv or Nissan). Originally, this feast had three distinct parts: The Passover itself, the Feast of Unleavened Bread, and the Feast Day of the Sheaf of First Fruits. These eventually became known as a single festival.

Historical Background: The First Passover

The Passover commemorates the single most important event in Jewish history: the redemption from Egyptian slavery. 430 years earlier, God had called Abraham to leave his native country and go to the Land of Canaan. There, the Lord promised to make him into a great nation; Canaan was to be an everlasting possession to him and his descendants (Gen 17:5, 8).

Many years later, a severe famine drove Abraham's descendants, Jacob and his family, to Egypt. There, the children of Israel initially prospered and multiplied, but later they were enslaved by Pharaoh who ruthlessly oppressed them. God saw their affliction and heard their cry, and He appointed Moses as their leader to bring them out of Egypt into the land that He had promised to their forefathers (Exod 3:7-10).

Despite nine ruinous plagues inflicted upon Egypt, Pharaoh hardened his heart and refused to let the Israelites go - until a decisive tenth plague on the firstborn sons became the occasion for the institution of the Passover and the beginning of Israel's redemption. On the tenth day of the first month, the head of each Israelite household was to take a year-old male lamb without defect and set it aside until the fourteenth day. On the fourteenth day at twilight, he was to slaughter the lamb and sprinkle its blood on the doorposts and lintel of the houses. The Israelites were to eat the meat roasted over fire, along with bitter herbs and unleavened bread. They were to eat in haste, ready to leave Egypt at God's command (Exod 12:1-11).

At midnight the Lord struck down all the firstborn sons in the houses that were not marked with the blood of the lamb. The blood was a sign for the Israelites and for God, so that when He saw it, he "passed over" (hebrew: pasach) the marked houses of the Israelites while bringing judgment on Egypt (Exod 12:23). This finally convinced Pharaoh to let the Israelites go; and so their long journey in the wilderness towards the Land of Canaan began.

New Testament Fulfillment: The Paschal Lamb of God

Just as the Passover was the first and most significant event of God's redemption of Israel from Egypt, Christ's Paschal Mystery is the central event of God's redemption of the world from sin.

At the heart of the Passover was the blood of the lamb that had to be shed as evidence of death, which was necessary for atonement (Lev 17:11). Likewise, the New Testament Passover centers around "the Lamb of God who takes away the sin of the world" (John 1:29). Although the world still lies under God's judgment, redemption from sin is now offered in "the precious blood of Christ, like that of a lamb without blemish of spot" (1 Peter 1:19). Just as the paschal lamb had to be without defect, only a perfect, sinless Messiah could offer his life to atone for the sins of mankind (John 8:46; 1 Peter 2:22; 1 John 3:5). Just as the whole community of Israel had to kill the lamb (Exod 12:6), so the Sanhedrin, the priests, and the crowds all called for the crucifixion of Jesus (John 19:15).

The Passover lamb had to be roasted by fire. Fire in Scripture speaks of God's judgment. Isaiah foretold that the servant of the Lord would bear the sins of many and would be stricken for the transgression of his people (Isa 53:8, 12). Jesus the Messiah suffered the fire of God's wrath and judgment. Yet none of his bones were broken (John 19:33), just as no bone of the Passover lamb was to be broken (Exod 12:46).

The blood also had to be sprinkled on the doorposts (Exod 12:7) in order for it to be efficacious on each household. Likewise, the blood of Christ must be applied to every person’s life through faith and baptism, which is the door to the other sacraments. Jesus is both the Lamb and the blood-sprinkled door protecting us from God's wrath. In his death, He is the Lamb, but in his resurrection, he is the door (John 10:9), the entrance into the household of God.

One also had to be circumcised to eat the Passover (Exod 12:48-49). Circumcision was the sign and seal of the Abrahamic Covenant (Gen 17), the sign of a covenant relationship with the Lord. In the New Covenant, only one who has entered into a covenantal relationship with Christ through baptism may partake of the Eucharist - the new Passover (1 Cor 11:29). Baptism is the new circumcision (Col 2:11-2), the true circumcision of the heart in the spirit and not of the flesh (Deut 30:6, Gal 6:15).

Moreover, the Israelites had to eat the lamb in order to be protected from judgment. Likewise, Christians must eat the lamb in order to fully participate in the Lord’s Paschal Mystery. As Jesus said, “unless you eat the flesh of the Son of man and drink his blood, you have no life in you” (John 6:53). In the Eucharist, Catholics truly consume the Body of the Lamb of God as they relive His Paschal Mystery, just as every Jew celebrating the Passover should consider the redemption from Egypt not merely as an event of the past, but as a personal redemptive experience:

In every generation let each man look on himself as if he came forth out of Egypt. As it is said: "And you shall tell your son...it is because of what the Lord did for me when I came forth out of Egypt" (Exod 13:8)[1]

Finally, the body of the lamb had to be eaten...

- in one night. Likewise, Jesus, our Passover Lamb suffered and died in one night.

- with unleavened bread. Leaven is often associated with sin in Scripture (see below). Just as no leaven could be found at Passover, there was no sin in Jesus.

- with bitter herbs. The bitter herbs symbolized the hardships that the Israelites endured under the Egyptian rule; they also represent the bitter suffering and death of Jesus on the cross.

- in haste, with loins girded, shoes on their feet and staff in hand. Salvation is the beginning of a journey in which we must redeem time, have the waist girded with truth, the feet shod with the preparation of the gospel of peace, and the sword of the Spirit in hand (Eph 6:13-17).

The Feast of Unleavened Bread (Matzot)

Let us, therefore, celebrate the festival, not with the old leaven, the leaven of malice and evil; but with the unleavened bread of sincerity and truth. (1 Cor 5:8)

Historical Background

The second part of the Passover is called the Feast of Unleavened Bread, which lasts seven days. Each household had to remove all leaven from the house during this time. For seven days, no leaven was to be found in the house; anyone who ate something with leaven in it was to be cut off from Israel. The first and the seventh days were Sabbath days, holy convocations when no work was to be done (Exod 12:15-20; 13:6-8)

The Significance of Leaven

Unleavened bread shall be eaten for seven days; no leavened bread shall be seen with you, and no leaven shall be seen with you in all your territory. And you shall tell your son on that day, ‘It is because of what the LORD did for me when I came out of Egypt.’ (Exod 13:7-8)

Leaven (or yeast) is a little bit of sourdough; when placed in a batch of dough it has the action of fermentation. Leaven puffs up and causes the dough to rise. It works silently, secretly and gradually, until the whole is leavened. Paul refers to this process when he asks the Corinthians "do you not know that a little leaven leavens the whole lump?" (1 Cor 5:6)

Spiritually, leaven in Scripture often symbolizes sin - that which is evil either in doctrine or practice. As with natural leaven, only a little bit is necessary to spread to the whole person. Jesus repeatedly warned the disciples to beware of the leaven of the Pharisees (hypocrisy, cf. Luke 12:1), of the Sadducees (disbelief in the resurrection, cf. Matt 16:12, Acts 23:6-8), and of Herod (worldliness, cf. Mark 8:15). Paul warned about the leaven of sensuality in the Corinthian church (1 Cor 5:1-13), and of legalism in the Galatian church (Gal 5:9).

Thus, for the Hebrews, the putting away of all leaven symbolized breaking the old cycle of sin and starting out afresh from Egypt to walk as a new nation before the Lord. They did not put away leaven in order to be redeemed; rather, they put away leaven because they were redeemed. The same principle applies to the redeemed of the Lord of all ages: Salvation is of grace, 'not by works, so that no one can boast' (Eph 2:8)"[2].

Sanctification is the result of redemption, not a prerequisite. Christians spiritually keep this feast by putting away all evil doctrine and all evil practice and living a sanctified life. The life that is set apart - separated from sin - is the unleavened life. Catholics also keep the Feast by partaking of the Eucharist. In the sacrament, Christ is the Bread of Life (John 6:35), the unleavened bread of sincerity and truth (1 Cor 5:8).

From the Passover to the Eucharist

This day shall be for you a memorial day, and you shall keep it as a feast to the LORD; throughout your generations you shall observe it as an ordinance for ever. (Exod 12:14)

After the Israelites entered the Promised Land, the Passover served as a perpetual memorial of what God had done for them (Exod 12:14). They were to remember the Lord as they enjoyed the goodness and blessings of the land, perpetually retelling the events of His great redemption. One of the first things they did after arriving in Canaan was to celebrate the Passover under the command of Joshua (Josh 5:10). For centuries after the Exodus until today, the Passover celebration - or its neglect - stood as an indicator of the Jewish community's spiritual condition (cf. 2 Kgs 23:21-23; Ezra 6:19-20).

By the time of Christ, the Passover observance included new customs that had been added to the prescriptions of the Torah. A set form of service called the Seder eventually became standardized. The ceremony included ritual hand washings and set prayers. The celebrants drank four cups of wine as a symbol of joy. The story of the Exodus was retold, and the lamb, the bitter herbs, and the unleavened bread were explained. It is within this context that Jesus celebrated the Last Supper and instituted the Eucharist, redefining forever the meaning and symbolism of the feast.

At the moment of the ritual hand washing, normally seen as a sign of honor for the host, Jesus stunned his disciples by washing their feet, setting an example of love and humility as he took on the role of a servant (John 13:1-11).

Jesus then broke the bread, saying "This is my Body which is given for you: do this in remembrance of me" (Luke 22:19). These words now so familiar to us were shocking to Jesus' disciples. The unleavened bread would never again have the same significance. It became the Body of the Messiah broken for them. He then took the cup - probably the third cup of the Seder, representing redemption - and said "This cup is the new covenant in my blood, which is shed for you" (Luke 22:20), telling them, in effect: "I am the true Passover Lamb offered up for your redemption. This wine is my blood, poured out as an atonement for you."

Since the destruction of the Temple in AD 70, the Jews have faithfully preserved the Passover ritual. Today, its celebration is still living and vibrant. Still, one notable absence cannot go unnoticed: the main course of the Feast, the Passover lamb, has been missing since the end of the Temple sacrifices. The lamb is now usually represented by the roasted shank bone of a lamb on the Seder plate. This is a significant omission because the Torah stipulates that there is no atonement nor forgiveness without the shedding of blood (Lev 17:11).

Another ritual bears a special significance, that of the afikomen. In the modern Seder, three pieces of matzah (unleavened bread) are stacked on a plate, each piece separated with a napkin; the three wafers are then covered with a cloth. In the course of the evening, the host takes out the middle wafer and breaks it in half. He puts one of the halves back in the unity and hides the second half, called the afikomen, somewhere where the children will find it at the end of the meal. It is then eaten reverently, as a replacement and in memory of the Pascal Lamb. Several popular theories attempt to give a meaning to this ritual, but contemporary Judaism gives no set interpretation or satisfactory explanation. One possible meaning of the ritual, however, could date back to the days of the early Jewish Christians, before they were excluded from the Jewish community. This interpretation sees the three pieces of matzah as the eternal unity of God: the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit. The breaking of the middle matzah signifies the death of the Messiah; hiding it symbolizes his burial, and finding it again - his resurrection.

The Feast of the Sheaf of Firstfruits (Bikkurim)

But in fact Christ has been raised from the dead, the first fruits of those who have fallen asleep. For as by a man came death, by a man has come also the resurrection of the dead. For as in Adam all die, so also in Christ shall all be made alive. But each in his own order: Christ the first fruits, then at his coming those who belong to Christ. (1 Cor 15:20-23)

The last part of the Feast of Passover is the day of the Sheaf of Firstfruits (Lev 23:9-14). After they arrived in the Promised Land, the Israelites were to bring a sheaf of the first grain of the harvest to the priest. The priest would then wave the sheaf before the Lord on the day after the Sabbath. Certain prescribed offerings were also to be presented along with the sheaf. No one was to eat the bread or roasted grain of the new harvest until that sheaf had been presented to the Lord and accepted for Israel.

This feast marked the beginning of the harvest season. First came the barley crop at Passover, then the wheat at Pentecost, and finally the fruit harvest at the end of the year, at the time of the Feast of Tabernacles. This first sheaf offered to the Lord was a forerunner sheaf, a sample sheaf of the coming harvest.

A sheaf in Scripture sometimes represents a person. Joseph saw in his dream eleven sheaves bow down to his sheaf, representing his brothers who would eventually bow down to him (Gen 37:5-11). Psalm 126 speaks of the sower sowing in tears, but later reaping with songs of joy, carrying sheaves with him. Jesus Christ is the Lord of the harvest (Luke 10:2). In his first coming, he sowed in tears through his suffering and dying on the cross. In his second coming, he will reap with joy, bringing his sheaves with him - the redeemed souls which come to fruition by the gospel.

Jesus is also our sheaf of firstfruits. In Israel, the firstfruit or firstborn was always the choicest, the first, and the best of what was to follow. It was always to be consecrated to the Lord (Exod 13:2, 11-13). Jesus is the firstborn of the Blessed Virgin Mary (Matt 1:23-25), the first-begotten of the Father (Heb 1:6), the firstborn among many brothers (Rom 8.29), and the firstborn from the dead (Col 1:18). Just as the first sheaf had to be waved before God and accepted by Him, God the Father manifested His acceptance of Jesus at his baptism, saying "You are my Son, whom I love; with you I am well pleased" (Luke 3:22).

The waving of the sheaf before God on the day after the Sabbath - Sunday - is a remarkable foreshadowing of the resurrection, which happened on the morning of the first day (Matt 28:1). Christ is the firstfruit of the resurrected saints and the first sheaf of the harvest that is to come.

The Feast of Weeks or Pentecost (Shavuot)

When the day of Pentecost had come, they were all together in one place. And suddenly a sound came from heaven like the rush of a mighty wind, and it filled all the house where they were sitting. And there appeared to them tongues as of fire, distributed and resting on each one of them. And they were all filled with the Holy Spirit and began to speak in other tongues, as the Spirit gave them utterance. (Acts 2:1-4)

The Feasts of Passover, of Unleavened Bread, and of the Sheaf of Firstfruits were the feasts of the first month or early spring. For the Israelites, they commemorated the deliverance out of Egypt and the beginning of their walk with God towards the Promised Land. Similarly, for Christians, the death of the Lamb of God on the cross, his burial, and his resurrection are the starting point for a relationship with Him. The Passover foreshadows redemption, justification, regeneration, and adoption. The Feast of Unleavened Bread calls us to sanctification and separation from evil, while the Feast of the Firstfruits calls us to walk in resurrection and newness of life.

But these feasts are only the beginning. The next major holy day is the Feast of Weeks, which commemorates the giving of the Law at Mount Sinai for Israel, and the outpouring of the Holy Spirit upon the Church for Christians.

After crossing the Red Sea, the Israelites were led by the pillar of fire to the foot of Mount Sinai. They arrived there on the first day of the third month (Exod 19:1), and God told Moses to sanctify the people and have them ready for the third day (Exod 19:11). Since the Exodus began on the 15th day of the first month, it follows that there are 49 days between the Passover and the Sinai theophany (15 days in the first month, 30 days in the second month, and 4 days in the third month). On the next day, the 50th day, the Lord gave the Ten Commandments to Israel. This event is commemorated in the Feast of Weeks or Shavuot, celebrated seven weeks after the Feast of the Firstfruits (Lev 23:15-16):And you shall count from the day after the sabbath, from the day that you brought the sheaf of the wave offering; seven full weeks shall they be, counting fifty days to the day after the seventh sabbath; then you shall present a cereal offering of new grain to the LORD. (Lev 23:15-16)

The name "Pentecost" - meaning "fiftieth" - is its Greek name of this festival. After the Lord's resurrection on the Day of the Sheaf of Firstfruits, he appeared to his disciples for forty days (Acts 1:3) before ascending to heaven (Acts 1:9). The disciples waited for another 10 days in prayer in the upper room until the fiftieth day - the Feast of Shavuot - when the Holy Spirit was poured upon them. Kevin Conner states:

As Israel experienced the giving of the Law at Mt. Sinai 50 days after leaving Egypt under Passover, so the disciples experienced the coming of the Holy Spirit to write His laws 50 days after the completion of Passover by the resurrection of Christ. And again, as the Feast of Pentecost was celebrated 50 days after the waving of the sheaf of firstfruits, so the Holy Spirit was poured out on the 50th day after the resurrection of Christ Jesus. Truly a remarkable fulfillment of the Feast of the Fiftieth Day in the third month![3]

Significantly the number fifty represents freedom and deliverance in the Bible. In the year of Jubilee, celebrated every 50th year in Israel (Lev 25:8), slaves were set free, debts were canceled, families were reunited, and liberty was proclaimed throughout the land at the sound of the Jubilee trumpets. For Jews, the Feast of Shavuot fifty days after their deliverance from Egypt was a celebration of liberty from the house of bondage. For Christians, Pentecost means liberty from "the ministry that brought death, engraved in letters on stone" to the glorious freedom of the ministry of the spirit that brings righteousness (2 Cor 3:7-11).

There are other parallels between Shavuot and the Christian Pentecost. Supernatural manifestations were present both times. On Mount Sinai there was thunder and lightning, thick clouds, fire and smoke (Exod 19:16-19). In the upper room came a violent wind and tongues of fire descended onto the disciples (Acts 2:2-3). After the giving of Torah, 3000 people were slain because of idolatry (Exod 32:28). After the giving of the new law of the Spirit, 3000 people were baptized and added to the Church (Acts 2:41). At Mount Sinai, God revealed himself as awesome, almighty and unapproachable, and to see Him face to face would have meant instant death (Exod 19:21). At Mount Zion, "the heavenly Jerusalem, the city of the living God" (Heb 12:22) where Jesus instituted the New Covenant, God not only becomes approachable; He even desires to dwell in us through his Spirit by making us perfect, thanks to Jesus "the mediator of a new covenant, and to the sprinkled blood" (Heb 12:24). We see again a connection between blood and covenant: Under the Old Covenant, Moses sprinkled sacrificed blood on the people and the book (Exod 24:8). Under the New Covenant, Jesus provides his own blood, poured out for many for the forgiveness of sins (Matt.26:28).

Interestingly, the Feast of Weeks required the people to bring an offering of two loaves of bread baked with leaven. This seems to be a curious requirement, for as we have seen above, leaven usually represents sin in the Bible, and it is to be completely disposed of for the Passover. Moreover, it was usually forbidden to bring any kind of offering containing leaven (Lev 2:4, 11). Could this be a typological recognition that sin has not yet been eradicated from the Church despite the indwelling of the Holy Spirit? At the Passover, the bread had to be unleavened since it represented the sinlessness of the Lamb of God. But here the loaves could represent the believer who is still subject to human weakness and thus still imperfect in his service to the Lord.

Finally, the Feast of Weeks - the second major harvest festival of the year - is also called the "Feast of Harvest" (Exod 23:16). The wheat crop was brought in during that time, and it was a time of rejoicing and thanksgiving to the Lord. The antitypical fulfillment of this harvest can also be seen at Pentecost when many souls are harvested in this season of the "early rains" of the Holy Spirit. The feast points to the expectation of the final and greatest harvest that is still to come in the fall at the Feast of Tabernacles.

The Feasts of the Seventh Month

Just as the Passover includes three distinct feasts, so the festive season of the seventh month (in late September or October) includes three festivals: These are the Feast of Trumpets, the Day of Atonement, and the Feast of Tabernacles.

These fall feasts differ from the spring festivals as to their messianic fulfillment. Whereas the Passover is fulfilled in Christ’s Paschal Mystery, and the Feast of Weeks in the outpouring of the Holy Spirit at Pentecost, it appears that the fall feasts have not yet been fulfilled. There is a hint of this in the Jewish calendar: While the spring feasts of Passover and Pentecost are only seven weeks apart, the fall feasts come much later in the year, after the dry summer months. This long, barren period between the spring and fall festivals could be a foreshadowing of the history of both Israel and the Church. While the spring feasts mark the beginning stages of God’s plan of salvation, the fall feasts mark its consummation. These feasts, therefore, have an eschatological significance.

After their deliverance from Egypt (Passover), the Israelites only took about 45 days to cross the Red Sea and arrive at Mount Sinai, where the Lord gave them the Ten Commandments (Pentecost). From there, God intended to bring His people into the Land of Canaan, where they would celebrate the fall harvest festivals and partake of the fruit of the land. But the Israelites rejected God's promises at Kadesh-Barnea and even wanted to return to Egypt. Because of their rebellion and unbelief, God condemned them to wander in the desert for forty years until the first generation died out (Num 13-14). Only the second generation, under the leadership of Joshua, was able to enter the land and enjoy its blessings.

Similarly, the Church had a powerful beginning and experienced rapid growth after the Paschal Mystery and Pentecost. But just as Israel’s journey was prolonged because of their unbelief, so the Church, “at once holy and always in need of purification,” followed suit in her journey through history. While the first Christians expected Jesus to return soon (Matt 24:3, 24), we are still awaiting His second coming two thousand years later (2 Thess 2:1-2; 2 Pet 3:4-10). Generations of Christians died without experiencing the eschatological fulfillment of the fall festival, which will occur at the consummation of the present age when the Lord returns.

Let’s now examine more closely these fall feasts and their eschatological significance.

The Feast of Trumpets (Rosh Hashanah)

Then will appear the sign of the Son of man in heaven, and then all the tribes of the earth will mourn, and they will see the Son of man coming on the clouds of heaven with power and great glory; and he will send out his angels with a loud trumpet call, and they will gather his elect from the four winds, from one end of heaven to the other. (Matt 24:30-31)

The Feast of Trumpets takes place on the first day of the seventh month; it is "a day of solemn rest, a memorial proclaimed with blast of trumpets, a holy convocation" (Lev 23:24). The Torah does not specify any particular reason for this feast. It merely states that no work should be done on this day (Lev 23:25), and specific sacrifices should be offered (Num 29:1-6). Traditionally, the blowing of the trumpets has become a call to start preparing for the atonement of sins that is to come nine days later on Yom Kippur. It is also the beginning of the civil year in Israel, and thus the feast in time became known as Rosh Hashanah ("the head of the year").

The blowing of trumpets has a variety of uses in the Bible: it marks the calling of assemblies, the sounding of alarms, imminent war, days of gladness, solemn assemblies, feasts, and the beginning of months (Num 10:1-10). Trumpets were blown, for example, at the fall of Jericho (Josh 6), or when the Ark of the Covenant returned to Jerusalem (1 Chron 15:24-29). At times, the trumpet symbolizes the prophetic voice, the spoken Word of the Lord coming to His people.

Although the Feast of Trumpets is not explicitly mentioned in the New Testament, there are several references to the blowing of trumpets, which tends to be associated with the final judgment, the second coming of Christ, and the resurrection of the dead (Matt 24:31; 1 Cor 15:51-52; 1 Thess 4:16; Rev 8:1-9; 11:15).

Today, the shofars (trumpets made of ram's horns) are calling Israel to regather as a nation. They may also symbolize the Lord calling His Church to make herself ready for the turbulent times of intense spiritual warfare that will precede God's final judgment at the consummation of history.

The Day of Atonement (Yom Kippur)

But when Christ appeared as a high priest of the good things that have come, then through the greater and more perfect tent (not made with hands, that is, not of this creation) he entered once for all into the Holy Place, taking not the blood of goats and calves but his own blood, thus securing an eternal redemption. (Heb 9:11-12)

The most solemn of all Jewish feast days is the Day of Atonement, which occurs on the tenth day of the seventh month. On that day, the people of Israel were to hold a sacred assembly, "afflict their souls", fast, pray, and offer a fire offering to the Lord. Work was strictly forbidden: anyone caught doing work on that day would be cut off from among his people (Lev 23:26-32).

Yom Kippur was the only day of the year when the high priest entered the Holy of Holies to make atonement for himself and his household, for the entire nation, and for the sanctuary. The blood of the sin offering on the great Day of Atonement brought about the cleansing of all sin, iniquity, and transgression, thus reconciling Israel to their God.

The high priest first offered a bull for a sin offering to make atonement for himself and his household. He then took two goats and cast lots to decide which one was to be sacrificed to the Lord, and which one would be taken into the wilderness to be released. After this, the high priest took the blood of the bull and sprinkled it before the atonement cover in the Holy of Holies, through a screen of incense smoke. The smoke concealed the atonement cover, for if he were to see it, he would die. Next, the high priest killed the Lord's goat for a sin offering and offered it for the people, as he did with the blood of the bull. The blood of the goat atoned for the sins of the nation of Israel. The high priest would also make atonement for the Holy of Holies, the Tabernacle, and the Altar because of their defilement due to the uncleanness of the Israelites. (Lev 16:1-19)

Once the atonement was completed, the high priest would lay his hands on the head of the second goat and confess over it all the sins, iniquities, transgressions and uncleanness of Israel. The scapegoat would then be released in the wilderness, symbolically carrying away the sins of the people (Lev 16:20-22). Finally, the bull and goat for the sin offerings were to be taken outside the camp and burned (Lev 16:27).

The Epistle to the Hebrews explains why this sacrificial system was imperfect and temporary, and how it is fulfilled in Christ. First, God was never pleased with animal sacrifices (Heb 10:8; cf. Ps 40:6). The fact that so many animals were sacrificed over and over each year indicates that these were insufficient to take away the sins of the people. The animals sacrifices only "covered" the sins of Israel until the ultimate atonement sacrifice would be revealed:

For since the law has but a shadow of the good things to come instead of the true form of these realities, it can never, by the same sacrifices which are continually offered year after year, make perfect those who draw near. Otherwise, would they not have ceased to be offered? If the worshipers had once been cleansed, they would no longer have any consciousness of sin. But in these sacrifices there is a reminder of sin year after year. For it is impossible that the blood of bulls and goats should take away sins. (Heb 10:1-4)

By contrast, Christ's sacrifice perfectly atones for the sins of his people. "For by a single offering he has perfected for all time those who are sanctified," and "where there is forgiveness of these, there is no longer any sacrifice for sin" (Heb 10:14,18).

In addition to being the atoning sacrifice, Jesus is also our high priest, "holy, innocent, unstained, separated from sinners, and exalted above the heavens. He has no need, like those high priests, to offer sacrifices daily, first for his own sins and then for those of the people, since he did this once for all when he offered up himself" (Heb 7:26-27). Because he lives forever, "he holds his priesthood permanently," and "he is able to save to the uttermost those who draw near to God through him since he always lives to make intercession for them" (Heb 7:24-25).

Under the Levitical sacrificial system, God was remote and inaccessible. Only the high priest could come into his presence in the sanctuary on the Day of Atonement. Moreover, any mistake in the ritual would mean death. With Jesus' death on the cross, the veil at the entrance of the Holy of Holies in the Temple was torn from top to bottom, signifying that the way into God's presence was now open to all who believe through Christ (Matt 27:51).

Christ is also seen in the two goats - in the one that had to die to reconcile us to God, and in the scapegoat that carried our sins away.

Yom Kippur Today

The Day of Atonement remains the most solemn day of the year today for Jews. With no Temple, priesthood or sacrifices, however, Judaism has shifted the emphasis of the day to repentance, prayer, and charitable deeds, in order to obtain atonement. But just as the Jewish Passover is now lacking its sacrificed lamb, so is Yom Kippur now missing its heart, so to speak - the shedding of blood for the remission of sins (cf. Lev 17:11).

An interesting story from rabbinic tradition underlines this anomaly in the post-biblical Jewish celebration of Yom Kippur. The Talmud relates that a red ribbon was tied around the horn of the scapegoat; after the goat was released in the wilderness, the ribbon would turn white as a sign that God had accepted Israel's atonement ceremonies and forgiven their sins. But the Talmud acknowledges that something dramatic happened forty years before the fall of the temple in A.D. 70, which affected the efficacy of the atonement ritual:

Forty Years before the holy temple was destroyed, the lot of the Yom Kippur ceased to be supernatural; the red cord of wool that used to change white now remained red and did not change.[4]

Forty years before the destruction of the temple brings us to 30 AD, around the time when Christ was crucified. Some have suggested a correlation between Jesus' death and the red ribbon that no longer turned white, namely, that with the atoning death of the Messiah, the Yom Kippur sacrificial ritual lost its efficacy. Shortly thereafter, the Temple was destroyed and the Jews were dispersed.

The prophet Zechariah speaks of a day that has not yet come to pass when the house of David will mourn for “one who was pierced” – perhaps pointing to a future fulfillment of the Day of Atonement among the Jewish people:

And I will pour out on the house of David and the inhabitants of Jerusalem a spirit of grace and supplication. And they will look on me, whom they have pierced, and they will mourn for him as one mourns for an only child, and grieve bitterly for him as one grieves for a firstborn son." (Zech 12:10)Yom Kippur thus foreshadows not only the Second Coming and final judgment, when the Lord will separate the sheep from the goats and render judgment to each person (Matt 25:31-46). It also anticipates the day when “all Israel will be saved” in recognizing Jesus, the atoning sacrifice and eternal high priest of Israel (Rom 11:26; CCC 674).

The Feast of Tabernacles (Sukkot)

On the last day of the feast, the great day, Jesus stood up and proclaimed, “If any one thirst, let him come to me and drink. He who believes in me, as the Scripture has said, ‘Out of his heart shall flow rivers of living water.’ ” (John 7:37-38)

The last harvest feast of the year is the Feast of Tabernacles, beginning on the 15th day of the seventh month and lasting seven days. After gathering the crops, the people were commanded to celebrate and rejoice before the Lord. They were to build booths (sukkot) and live in them for the duration of the Feast as a reminder of the time when they lived in booths on their journey through the desert during the Exodus. For the seven days, they were to present offerings to the Lord; the first and the eighth day were additional Sabbath days when no work was to be done (Lev 23:33-36, 39-43).

After the spring rains and the corn harvest at the time of Passover and Pentecost came the dry season when generally no rain fell. By the seventh month, the ground was hard and barren, and with the last harvest came hope for the much-needed fall rains, which were understood to be a reward for the people's obedience to God. The Jews likely had the words of the Torah in mind as they approached this season:

And if you will obey my commandments which I command you this day, to love the LORD your God, and to serve him with all your heart and with all your soul, he will give the rain for your land in its season, the early rain and the later rain, that you may gather in your grain and your wine and your oil. And he will give grass in your fields for your cattle, and you shall eat and be full (Deut 11:13-15).

In the days of the Temple, an important part of the Feast of Sukkot was the daily water libation ceremony, when water was drawn from the pool of Shiloah, carried up to the Temple in a joyful procession, then poured on the altar in order to invoke God’s blessing for rain.

It is within this context of praying for rain that Jesus announced on the last day of Sukkot that he is the source of living water that can quench man's desire for eternal life (John 7:37-38; cf. 4:13-14). Without this spiritual water - the rain of the Holy Spirit - man would drink and remain spiritually thirsty. The fall rains and the harvest of the Feast of Tabernacles also point to the end-time outpouring of the Holy Spirit and the great final harvest of souls out of all nations that Jesus referred to in his parable of the weeds (Matt 13:24-30, 37-43). Conner states: "Thus under the closing days of grace, in the end of this age, the harvest will take place. The same rain that ripens the wheat also ripens the tares. The same rain that matures the righteous will also mature the wicked."[5]

The apostle John had a vision of this end-time harvest of the righteous and the wicked (Rev 14:13-20). Jesus expressed concern that there are too few workers willing to gather in the plentiful harvest from the ripe fields (Matt 9:37-38, John 4:35). Timing is crucial for a successful harvest. If the crop is not harvested in time, it may easily be lost. The same goes for the many souls who were ripe for harvest throughout the ages, but were lost because there were no workers available to bring them the gospel.

After the harvest was brought in and the booths were built, the Israelites dwelled and rejoiced in them for the duration of the feast. This was not only a commemoration of their fragile existence and of God's providence in the desert; it was also a reminder of the present fragility of their life even after they had settled in the land. They were not to trust in their houses or in the land that could be easily taken away, but in God who still preserved them as he had done so during the Exodus. The booths reminded them - as they still remind Jews today - that they are but pilgrims and strangers on earth. Likewise, the Christian is a pilgrim and a stranger in this world, looking for a city whose builder and maker is God, as did Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob (Heb 11:10-16). Just as the tabernacles were temporary dwelling places, so believers are reminded that their earthly, physical body is but a temporary dwelling place that will one day be put off and replaced by a new and heavenly house, the eternal dwelling place of an immortal, glorified body (2 Cor 5:1-5).

The eschatological nature of this feast is seen in the words of the prophet Zechariah, who writes that those who survive the final battle at the end of history “shall go up year after year to worship the King, the Lord of hosts, and to keep the feast of booths” (Zech 14:16). On another level, the fullness of this feast will be experienced at the resurrection and glorification of the saints and the establishment of Christ's eternal, heavenly kingdom. Then we will look back at the fragile, earthly pilgrimage of this life and remember the goodness of the Lord, rejoicing in His glory. Then the Tabernacle of God will be with men: "He will dwell with them, and they shall be His people" (Rev 21:1-4).The Post-Mosaic Festivals

In addition to the seven appointed feasts of the Torah, two other major Jewish festivals should be mentioned.

The first post-mosaic feast is the Feast of Purim. Its origins go back to the Persian exile and to the story of Esther under the rule of King Ahasuerus (Xerxes) in the fifth century B.C. Purim commemorates how the Jews overcame Haman's plot to exterminate them, thanks to the intervention of Mordecai and Esther. This feast is not mentioned in the New Testament

The second post-mosaic feast is the Feast of Dedication or Hanukkah. Celebrated for eight days beginning on the 25th day of the month of Kislev, this feast dates back to 165 BC, and its origins can be found in the Books of Maccabees. Hanukkah celebrates the deliverance of Israel in one of the nation's darkest times. Israel was under Seleucid domination, and the Seleucid king, Antiochus IV Epiphanes, began an aggressive Hellenization campaign that sought to destroy the Jewish religion and culture. Antiochus persecuted the Jews and desecrated the Temple by setting up altars to pagan gods and sacrificing pigs to them. Circumcision and practice of the Mosaic Law were outlawed, and many Jews compromised their faith and gave in the pressure of Hellenization so that the survival of Israel's Jewish and Biblical culture was severely threatened.

At this time of crisis, a priest named Mattathias remained faithful to the Lord, and he instigated a revolt carried out by his sons that would eventually defeat the Syrians and restore the legitimate Temple worship in Jerusalem. After the victory of the Maccabees, the Temple was cleansed and the sanctuary rededicated to the Lord. This is the origin of the name of the Feast of Dedication, or Hanukkah.

According to tradition, the Jews at that time found a jar containing a small amount of consecrated oil which miraculously burned for eight days, as the Temple menorah was lighted again. Today, the event is celebrated by lighting a special menorah with nine candles. In Jesus' time the feast was called the Festival of Lights[6]

This feast is only mentioned once in the New Testament: "And the Feast of Dedication took place at Jerusalem, and it was winter. And Jesus walked in the temple in Solomon's Porch." (John 10:22-23). Some have noted the parallels between the cleansing and illumination of the Temple at the time of the Maccabees, and how Jesus, "the true Light that enlightens every man" (John 1:9), cleanses and illuminates the hearts of his followers, who are living temples of the Holy Spirit.

Conclusion

Our brief study of the Jewish Feasts has provided a basic overview of how Christ is prefigured in Israel's Holy Days, revealing a glimpse of the richness of God's salvation plan for humanity. Studying the shadow that God revealed to Israel long before the coming of the Messiah helps Christians to better understand God's purposes for Israel and for the world as these were revealed in the fullness of time.

|

Feast |

Day and Season |

Original Significance for Israel |

Messianic Fulfillment |

|

Passover |

14th of 1st month |

Redemption from Egyptian bondage |

Paschal mystery; redemption from sin |

|

Unleavened Bread |

15th–21st of 1st month (early spring) |

Purging of leaven (symbol of sin) |

Cleansing from sin; sanctification |

|

Firstfruits |

Sunday of Passover (early spring) |

Thanksgiving for firstfruits; promise of harvest to come |

Resurrection: Christ is the first to rise from the dead (1 Cor 15:20-23) |

|

Feast of Weeks |

7 weeks after Firstfruits (late spring) |

Thanksgiving for first harvest; covenant and giving of the Law at Sinai |

Outpouring of Holy Spirit; “first harvest” of souls at birth of the Church (Acts 2:1-4) |

|

Feast of Trumpets (Lev 23:23-25) |

1st of 7th month |

Solemn assembly; begins the “Days of Awe” |

Final Tribulation and Second Coming |

|

Day of Atonement |

10th of 7th month (autumn) |

Solemn assembly for repentance and forgiveness |

Last Judgment; salvation of Israel |

|

Feast of Booths |

15th–21st of 7th month (autumn) |

Harvest celebration and memorial of booths in the wilderness |

Eternal Kingdom of God established |

© Copyright 2007 Catholics for Israel (revised August 2016)