The People of Israel, the Holy Land and the Koran

It is well known that the terrorist activities of fundamentalist Islamic groups in the Holy Land are specifically directed towards the disintegration of the Jewish State and the withdrawal of Jews from all the land they presently inhabit. In effect, irredentist groups such as Islamic Jihad, Hamas and Hezbollah aim for nothing less than to precipitate, through violence and terror, the third exile of the Jewish people, even before they have fully returned. Not only do these groups command growing support among the Palestinian people, but they also appear to influence the uncompromising stance taken by the leaders of the Arab nationalist parties in the region (the PLO/Fatah faction and the PFLP).

It is well known that the terrorist activities of fundamentalist Islamic groups in the Holy Land are specifically directed towards the disintegration of the Jewish State and the withdrawal of Jews from all the land they presently inhabit. In effect, irredentist groups such as Islamic Jihad, Hamas and Hezbollah aim for nothing less than to precipitate, through violence and terror, the third exile of the Jewish people, even before they have fully returned. Not only do these groups command growing support among the Palestinian people, but they also appear to influence the uncompromising stance taken by the leaders of the Arab nationalist parties in the region (the PLO/Fatah faction and the PFLP).

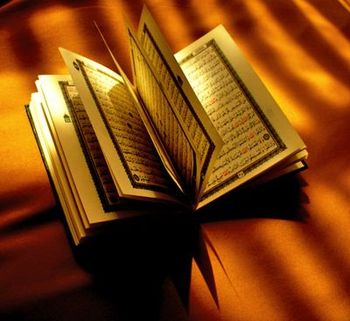

The rationale for their intention to destroy the Jewish State is derived from an ancient Islamic tradition demanding that Muslims take action to reclaim land that has been forcefully taken from them, and to this end a violent struggle, or ‘jihad’ is permitted. The principle is clearly stated in the Koran, as follows:

“Fight for the sake of God those that fight against you, but do not attack them first. God does not love aggressors. Slay them wherever you find them. Drive them out of the places from which they drove you” (The Cow 2:190-191).

And in another place:

“Permission to take up arms is hereby given to those who are attacked, because they have been wronged. God has power to grant them victory: those who have been unjustly driven from their homes, only because they said: ‘Our Lord is God’” (Pilgrimage 22:39-40).

The Koran is therefore interpreted as justifying a military struggle to re-conquer the lands that were relinquished by Muslim inhabitants during all the Arab-Israeli wars since the establishment of the Jewish State in 1948.

However, according to the rules of interpretation described in the Koran (‘Imrans 3:7), individual passages in this Book must be interpreted in the light of relevant passages in other parts of the text. Since there are a number of passages in the Koran stating that God has given the Holy Land to the Sons of Israel, there can be no religious justification for radical Islamic opposition to the Jewish presence in this land.

The first of these passages explicitly states that God assigned the Holy Land to the people led by Moses, adding that this land has not been given to any other nation:

“Bear in mind the words of Moses to his people. He said: ‘Remember, my people, the favour which God has bestowed upon you. He has raised up prophets among you, made you kings, and given you that which he has given to no other nation. Enter, my people, the holy land which God has assigned for you. Do not turn back, and thus lose all’” (The Table 5:20-21).

Although the Israelites were then forbidden to enter this land for forty years, on account of their lack of faith (The Table 5:26), the following passage confirms that they finally entered their land and were blessed by divine Providence:

“We settled the Israelites in a secure land and provided them with good things” (Jonah 10:93).

There are no statements in the Koran suggesting that this land was ever taken away from the Sons of Israel and given to another people. What is described, in fact, is the recurrent cycle of exile and return that has been such a major feature of their history. Evidently written after the start of the second exile of the Jews, the following passage explains the recurrence of their exile and return as the fulfilment of a prophecy recorded by Moses, and clearly prepares Muslims to expect a continuation of the same process:

“In the book [We gave Moses] We solemnly declare to the Israelites: ‘Twice you shall do evil in the land. You shall become great transgressors.’And when the prophecy of your first transgression came to be fulfilled, We sent against you a formidable army which ravaged your land and carried out the punishment you had been promised.Then We granted you victory over them and multiplied your riches and your descendants, so that once again you became more numerous than they. We said: ‘If you do good, it shall be to your advantage; but if you do evil, you shall sin against your own souls.’ And when the prophecy of your next transgression came to be fulfilled, We sent another army to afflict you and to enter the Temple as the former entered it before, utterly destroying all that they laid their hands on.We said: 'Your Lord may yet be merciful to you. If you again transgress, you shall again be scourged. We have made hell a prison-house for unbeliever’” (The Night Journey 17:4-8).

In this context of exile followed by the return of the Jewish people, the reference to the time when ‘their Lord may yet be merciful to them' is highly significant: it implies, and therefore anticipates, the future return of the Jewish people to the Holy Land.

However, this passage not only awakens the expectation of a future return of the Jews to their homeland, but also reveals that the author knew of the destruction of the second Temple in Jerusalem. This simple fact throws light on the identification of the ‘farther Temple’ (‘al-misjad al-aksa’) mentioned in a previous passage:

“Glory be to Him who made His servant go by night from the Sacred Temple [in Mecca] to the farther Temple whose surroundings We have blessed, that we might show him some of Our signs” (The Night Journey 17:1).

Since it was known to the prophet Mohammed that the Temple in Jerusalem lay in ruins, and no longer served as a Temple or place of worship (‘misjad’), it is inconceivable that the ‘farther Temple’ mentioned in connection with his ‘night journey’ could refer to that Temple. Indeed, the earliest interpreters of this passage understood it to be a reference to the prophet’s heavenly rapture, which is described in other parts of the text (cf. The Star 53:13-18). In this case, the ‘farther Temple’ simply refers to God’s Dwelling in heaven.

It was only later, at the end of the 7th century CE, that the 'farther Temple' came to be identified with the site of the Temple in Jerusalem. This was motivated by financial and political, but not religious, considerations, at a time when the 5th Umayyad Caliph, Abd el-Malik, wanted to encourage Muslim pilgrimage to his newly built shrine in Jerusalem (cf. The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Vol VII, p. 97, under MI‘RADJ ).

It is almost certain, therefore, that the prophet Mohammed had no personal connection to the Temple Mount in Jerusalem, and that he gave his followers no religious motives for claiming that site. In fact, in the passage quoted above concerning the recurrent, historical cycles of exile and return, it is implied that whenever the Lord again shows mercy to the descendents of the Israelites, they will not only return to their land, but will also rebuild their Temple, as they had done before.

There is one other passage in the Koran that is relevant to this discussion. It not only confirms the Koranic expectation of a return of the Sons of Israel to their ancient homeland, but also identifies this event as a sign of the imminent fulfilment of God’s promises concerning the world to come:

“We said to the Israelites: ‘Dwell in the land. When the promise of the hereafter comes to be fulfilled, We shall assemble you altogether’” (The Night Journey, 17:104).

It should be noted that the two expressions used in the Koran to refer to the return of the Jews to their homeland at the End of Time – the assembly of the people of Israel (17:104) and their experience of God's mercy (17:8) – are not unique to the Koran. These two expressions are found together in a reference to the same end-time event in the Second Book of Maccabees, written towards the end of the 2nd century BCE. In this book, the prophet Jeremiah is reported to have said that the place of the Ark will not be revealed“until God gathers his people together again and shows them his mercy. Then the Lord will disclose these things and the glory of the Lord and the cloud will appear…” (2Macc 2,7-8; NRSV). It is therefore quite probable that the author of the Koran was repeating a standard expression used by the Jews to refer to their future return and redemption.

The Koranic perspective on the relation of the people of Israel to the Holy Land can therefore be summarized as follows:

- The Holy Land was a unique gift from God to the people of Israel, and there is no indication that this gift has been withdrawn.

- God punishes the transgressions of the people of Israel by exiling them from their land. This punishment does not cancel their divine claims to this land, since it is followed by the return of their descendants, whenever the Lord chooses to show them mercy.

- The future return of the people of Israel to their land is prophesied in the Koran, and is a sign of the consummation of history and the imminent fulfilment of God’s plan for mankind.

In the Muslim religion the authority of the Koran is absolute (cf. The Cow 2:2; The Table 5:48) and severe warnings are directed to those who accept some parts, while rejecting others (cf. The Bee 15:89-93; The Cow 2:174). From the passages quoted above, it should therefore be clear to all Muslims that God intends to allow the descendants of Israel to return to their land, at a certain time. The fact that this time has now arrived should also be clear, for it is not possible to deny the massive immigration of Jews during the 20th century, and the establishment of a Jewish State in this land.

By opposing the return of the Jews and their re-occupation of the Holy Land, Muslims are indeed opposing the Will of God. Even their own Scripture attests to that very fact, confirming the divine promises that were made to Israel as recorded in the Bible.

(Quotations are taken from the Penguin Classics edition of the Koran, revised translation by N.J. Dawood, 1997)