Christ, the 'Glory of Israel'

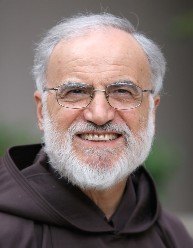

A Chapter from The Mystery of Christmas by Fr. Raniero Cantalamessa

The words of the Nunc Dimittis, as well as throwing light on the present problem of the relationship between the Church and non-Christian religions, also throws light on the problem of the relationship between the Church and the people of Israel, between Christians and Hebrews. If Christ is ‘the glory of his people, Israel’, we Christians must do all we can, first of all to acknowledge this ourselves and then to remove the obstacles that prevent Israel from acknowledging it. The first and most important obstacle to be removed is what St. Paul called ‘hostility’, ‘the dividing wall’ built on mutual incomprehension, diffidence and resentment, a wall that Jesus knocked down by his death on the cross (cf. Ep 2:14ff), but which must still be knocked down in deed, especially after all that has taken place in the last twenty centuries since Christ’s resurrection. St. Paul teaches us that the best way to a reconciliation between Israel and the Church is through love and esteem: ‘I am speaking the truth in Christ,’ he wrote to the Romans, ‘I am not lying; my conscience bears me witness in the Holy Spirit, that I have great sorrow and unceasing anguish in my heart. For I could wish that I myself were accursed and cut off from Christ’ (Paul separated from Christ!) ‘for the sake of my brethren, my kinsmen by race. They are Israelites and to them belong the sonship, the glory, the covenants, the giving of the law, the worship and the promises; to them belong the Patriarchs, and of their race, according to the flesh, is the Christ’ (Rm 9:1-5).

This was my own experience some years ago during my second pilgrimage to the Holy Land. The first thing I realized while still on the way there was that, as a Christian, I could not remain prisoner of the political judgements the world was passing on Israel in the atmosphere of attacks and reprisal which had started after the Israelites had conquered Arab territory but that I was obliged to love this people because ‘of their race, according to the flesh, is the Christ’. I should love them as Jesus, Mary, the Apostles and the whole of the primitive Church that came from the Jews did. It was a question of a kind of conversion to Israel that I had never experienced before then and, like all conversions, it exacted a change of mentality and heart.

This was my own experience some years ago during my second pilgrimage to the Holy Land. The first thing I realized while still on the way there was that, as a Christian, I could not remain prisoner of the political judgements the world was passing on Israel in the atmosphere of attacks and reprisal which had started after the Israelites had conquered Arab territory but that I was obliged to love this people because ‘of their race, according to the flesh, is the Christ’. I should love them as Jesus, Mary, the Apostles and the whole of the primitive Church that came from the Jews did. It was a question of a kind of conversion to Israel that I had never experienced before then and, like all conversions, it exacted a change of mentality and heart.

They, the Jews, are of the same blood as Jesus and it has been written that ‘no man ever hates his own flesh’ (cf. Ep 5:29). Jesus, who is a man like us even if he is God, is pleased if we Christians love one another and make excuses for his people even if they have not accepted him up to now. It often happened to me in my priestly ministry to get to know young boys and girls who were rejected and often even ill-treated by their parents for consecrating themselves to God and I saw the joy they experienced when I spoke well of their parents and tried to excuse them. They were happier than if I had said they themselves were completely right and had spoken about the injustice of their families. In the case of Jesus this is a consequence and a nuance of his real Incarnation which we must respect almost with modesty, just as we respect a family tragedy of a friend, mentioning it with discretion and sorrow. Israel is the first-born of God: ‘When Israel was a child, God loved him’ (cf. Hos 11:1) and we know that his love is ‘eternal’ (Jer 31:3).

Christians must love Israel not only in memory but also in hope; not only for what it was but for what it will be. Their ‘fall’, says the Apostle, ‘is not forever’ and God ‘has the power to graft them in again’ (cf. Rm 11:11-23). If their rejection means the reconciliation of the world, the Apostle continues, what will their acceptance be but life from the dead? Cf. Rm 11:15). Simeon said that Jesus was ‘for the fall and resurrection of many in Israel’ (Lk 2:34), which could be understood as: for the fall of some and the resurrection of others but also, as the Apostle meant: first for the fall and then for the resurrection of Israel. From the point of view of the Christian faith, all these centuries have been an extension of the wait, like a long detour in history, which we do not know how much longer is going to last, to arrive at when Jesus will again pass before Israel who will be able to say, as it is written: ‘Blessed is he who comes in the name of the Lord’ (cf. Lk 13:35).

On that journey these thoughts unexpectedly gave rise to the certainty in me that the Church is responsible for Israel! It is responsible in a unique way, differently from how it is to all other people. The Church alone guards in her heart and keeps alive God’s project for Israel. This responsibility of faith requires the Church to love the Jews, to wait for them, to ask, as it already does, their pardon for having in certain times hidden the true Jesus from them, that Jesus who loves them and who is their ‘glory’; that Jesus who taught us to let ourselves be scorned and killed rather than scorn and kill others. If the delay has been so long and painful, it has also undoubtedly been so through the fault of Christians. In this light we can understand the new signs we are experiencing in the Church, such as the constitution Nostra Aetate of Vatican Council II, the Pope’s visit to the Jewish synagogue in Rome, where he addressed the Jews as ‘elder brothers’, and, finally, the norms emanated by Rome to eliminate from the Christian catechism and preaching all those elements and ways of expression that could offend the sensitivity of the Jews and that are not required or justified by faithfulness to the Word of God.

Together with this responsibility which is relative to the past, there is another that concerns the present situation of Israel as a people and a state. Human and political judgements can be made on this present situation, as can judgements of theology and faith. Political judgement is that expressed by heads of States and which the U.N. also expressed in its turn. There is a whole area of different and opposing opinions open here, because all political thought, including that of Israel in the Old Testament, is in itself ambiguous, mixed with man’s sin even when God makes use of it for his plans of salvation, as happened in the Old Testament. The unresolved problem of the Palestinians driven out of their land makes these political judgements more of a condemnation of Israel than of approval. But, as I have already mentioned, Christians cannot stop at these political or diplomatic judgements. There is a theological or historical saving dimension of the problem which only the Church can feel. We share with the Jews the biblical certainty that God gave them the country of Canaan forever (cf. Gn 17:8; Is 43:5; Jer 32:22; Ezk 36:24; Am 9:14). We know, on the other hand, that ‘the gifts and the call of God are irrevocable’ (Rm 11:29).

In other words we know that God gave Israel the land but there is no mention of his taking it back again forever. Can we Christians exclude that what is happening in our day, that is, the return of Israel to the land of its fathers, is not connected in some way, still a mystery to us, to this providential order which concerns the chosen people and which is carried out even through human error and excess as happens in the Church itself? If Israel is to enter the New Covenant one day, St. Paul tells us that they will not do so a few at a time but as an entire nation, as ever-living ‘roots’. But if Israel is to enter as a nation, it must be a nation, it must have a land of its own, an organization and a voice in the midst of other nations of the earth. The fact that Israel has remained an ethnic unity throughout the centuries and throughout many historical upheavals is, in itself, a sign of a destiny that has not been interrupted but is waiting to be fulfilled. Many peoples have been driven out of their land over the centuries, but not one of them has been able to remain intact as a people in their new situation. Faced with this fact, we cannot but remember the words of God in Jeremiah: ‘If this fixed order departs from before me,’ (the order that governs the sun, the moon, the stars and the seas!) ‘says the Lord, then shall the descendants of Israel cease from being a nation before me forever’ (Jer 31:36). Even the huge cross that Israel carried on its shoulders is a sign that God is preparing a ‘resurrection’ for it, just as he did for his Son who represented Israel. The Jews themselves are not able to completely grasp this sign in their history because they have not completely accepted the idea that the Messiah ‘should suffer these things and enter into his glory’ (Lk 24:26), but we Christians must grasp it. When Edith Stein saw the tragedy that the Nazis were preparing for her people looming up, she recollected herself in prayer one day in the chapel and afterwards wrote: ‘There, beneath the cross, I understood the destiny of God’s people. I thought that those who know that this is the cross of Christ are in duty bound to take it upon themselves in the name of all the others.’ And she in fact took it upon herself, in the name of all the others.

The Church must therefore keep watch over these signs as Mary kept the words in her heart and meditated on them (cf. Lk 2:19). The Church cannot go back and take on the features of the old Israel with its strong bond between race, land and faith. The new salvation has been prepared ‘for all peoples’. What is required is that the Israel according to the flesh enter into and become part of the Israel according to the Spirit, without for this having to cease being Israel also according to the flesh which is its only prerogative. Thus St. Paul together with all those who have passed from the old to the new covenant can say: ‘Are they Hebrews? So am I! Are they Israelites? So am I! Are they descendants of Abraham? So am I!’ The Apostle even says: ‘I am a better one’ (cf. 2 Co 11:22ff) and he was right, at least according to the Christian faith, because only in Christ is the destiny of the Hebrew people fulfilled and its greatness discovered. We are not saying this in a spirit of proselytism but in a spirit of conversion and obedience to the Word of God because it is certain that the rejoining of Israel with the Church will involve a rearrangement in the Church; it will mean a conversion on both sides. It will also be a rejoining of the Church with Israel.

The reconstitution of the Jewish nation is a wonderful sign and opportunity for the Church itself, the importance of which we are not yet able to grasp. Only now can Israel take up again the question of Jesus of Nazareth and, to a certain degree, small but significant, this is what is happening. Quite a few in the Jewish religion have started to acknowledge Jesus as ‘the glory of Israel’. They openly acknowledge Jesus as the Messiah and call themselves ‘Messianic’ Jews, which is like saying ‘Christians’ in the original language, without bothering about the Greek translation. These help us to overcome certain gloomy prospects of ours, ‘making us realize that the great original schism afflicting the Church and impoverishing it is not so much the schism between East and West or between Catholics and Protestants, as the more radical one between the Church and Israel.

Sometimes in the New Testament, especially after the Resurrection, the turning to the Gentiles is spoken of as being a consequence of Israel’s rejection: ‘Since you thrust it from you, and judge yourselves unworthy of eternal life, behold we turn to the Gentiles. For so the Lord has commanded us, saying, “I have set you to be a light for the Gentiles”’. (Ac 13:46ff). But in the Nunc Dimittis at the beginning of the Gospel, the question is dealt with instead according to God’s original and marvellous plan in terms of harmony and mutual edification which has not yet been compromised. The fact that Christ is ‘a light for the Gentiles’ is not seen as a punishment for Israel but as its ‘glory’. How lovely it is, in the Christmas context, to put this original view of things back into the centre of the Church’s attention because, in the end, this will be fulfilled as nothing and no one can prevent God’s plan from being accomplished in the time established by him. One day Christ will also be, in deed, both ‘a light for the Gentiles and the glory of his people Israel’, as he already is by right! Simeon’s was not just a wish but a prophecy.